Laurel & Ash Farm Featured in DVEIGHT Magazine Issue 13

Courtesy of DVEIGHT.

By Alexandra Marvar Photos: Noah Kalina for DVEIGHT

DVEIGHT Magazine Issue 13

FLAVOR

WHEN LAUREL & ASH SELLS OUT OF SMALL-BATCH MAPLE SYRUP, THEY CAN GIVE UP, OR THEY CAN SCALE UP.

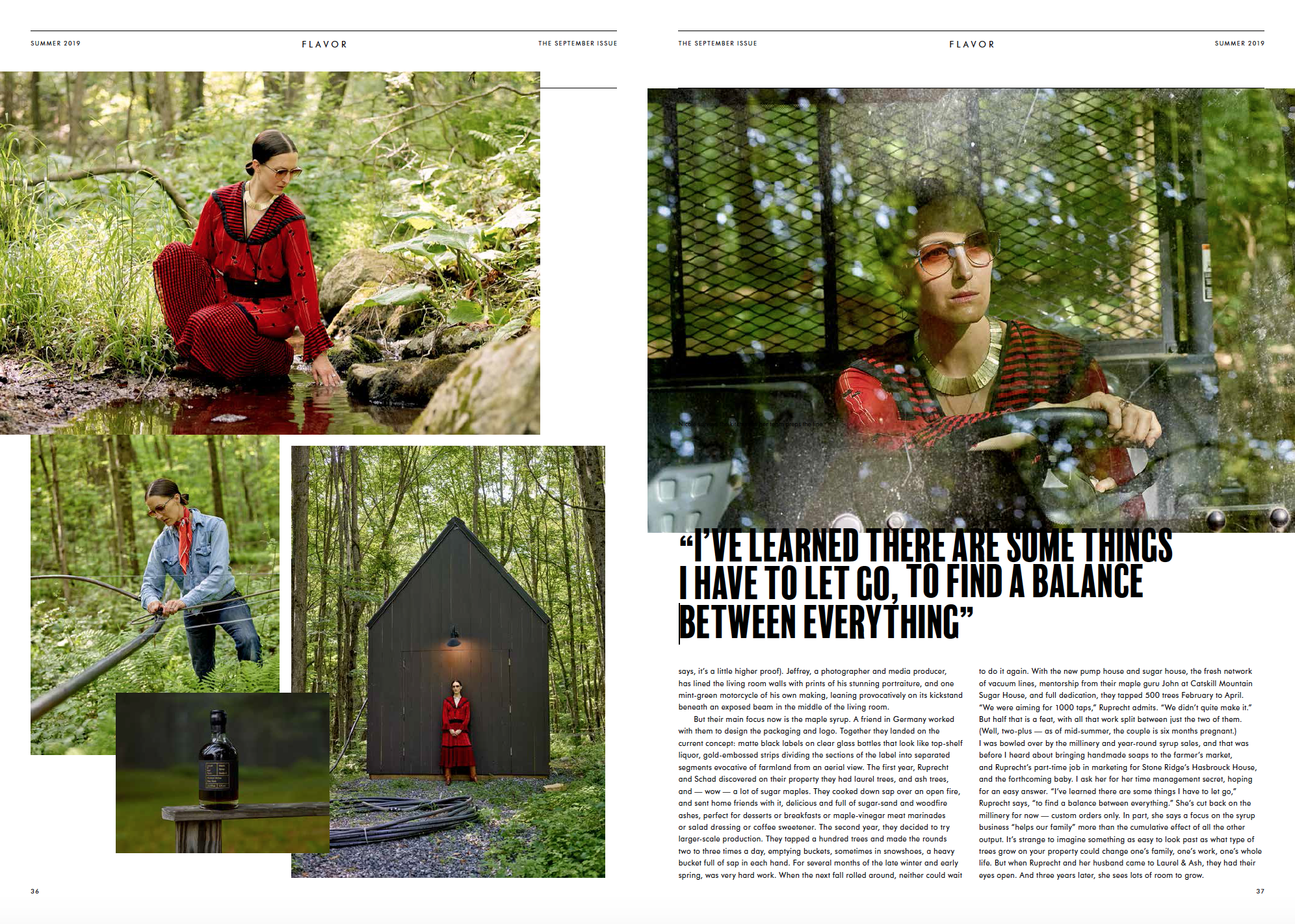

It’s the end of fennel season and I’m stepping lightly through the tall grasses behind ASHLEY RUPRECHT’s and JEFFREY SCHAD’s pump house toward one of their gardens. She points out black vernissage tomatoes, cucumbers, honey nut squashes, fennel, herbs, Mexican sour gherkins that look like watermelons the size of kumquats.

IT’S HOT IN THE WORLD, BUT COOL IN THE WOODS at Laurel & Ash Farm in Holmes, New York, and our stroll meanders across a tiny, lush corner of its 52 acres. Ruprecht leads me next into the sugar house her dad, an architect, designed for them. It matches the pump house — slate gray paint on tall, wide wood panels. While I’ve seen taps and buckets on a few trees in my day, the structures and the vast network of pipes and vacuum lines running in a vast grid between the trees across their property, like the physical evidence of a digital matrix, is next-level — Laurel & Ash’s maple syrup operation is no longer just a hobby.

Inside the sugar house are a series of shiny metal vats and vessels where a wood-fueled evaporator steams the water out of sap to make wood-fired syrup. “Our sap sauna,” Ruprecht says. She’s slender and elegant and wearing warm tint aviators and I’m having a hard time picturing the extreme physical work she does alongside her husband to make this operation go. 50 gallons of sap yield one gallon of syrup and to cook it down, this sugaring machine practically incinerates firewood. The size of a smart car’s cab, it gets refilled every seven minutes. Unluckily, a tornado took out hundreds of trees on their friends’ property recently, but luckily, Laurel & Ash will take firewood from wherever they can get it. “Jeffrey just cut six cords of wood over there. The next batch we make will be tornado-powered.”

The things that get made at Laurel & Ash Farm aren’t limited to fresh produce, shareable plant seedlings, and boutique, home-bottled maple syrup in four hues. Ruprecht turns out artful, high-end ladies’ hats under the banner Faeth Millinery — a business holdover from the couple’s past life in a Meeker Avenue loft in Greenpoint, which they said goodbye to in 2016 — anise-hyssop handmade bar soap; and hickory nocino (it looks like syrup — but, Ruprecht says, it’s a little higher proof). Jeffrey, a photographer and media producer, has lined the living room walls with prints of his stunning portraiture, and one mint-green motorcycle of his own making, leaning provocatively on its kickstand beneath an exposed beam in the middle of the living room.

But their main focus now is the maple syrup. A friend in Germany worked with them to design the packaging and logo. Together they landed on the current concept: matte black labels on clear glass bottles that look like top-shelf liquor, gold-embossed strips dividing the sections of the label into separated segments evocative of farmland from an aerial view. The first year, Ruprecht and Schad discovered on their property they had laurel trees, and ash trees, and — wow — a lot of sugar maples. They cooked down sap over an open fire, and sent home friends with it, delicious and full of sugar-sand and woodfire ashes, perfect for desserts or breakfasts or maple-vinegar meat marinades or salad dressing or coffee sweetener. The second year, they decided to try larger-scale production. They tapped a hundred trees and made the rounds two to three times a day, emptying buckets, sometimes in snowshoes, a heavy bucket full of sap in each hand. For several months of the late winter and early spring, was very hard work. When the next fall rolled around, neither could wait to do it again. With the new pump house and sugar house, the fresh network of vacuum lines, mentorship from their maple guru John at Catskill Mountain Sugar House, and full dedication, they tapped 500 trees February to April. “We were aiming for 1000 taps,” Ruprecht admits. “We didn’t quite make it.” But half that is a feat, with all that work split between just the two of them. (Well, two-plus — as of mid-summer, the couple is six months pregnant.) I was bowled over by the millinery and year-round syrup sales, and that was before I heard about bringing handmade soaps to the farmer’s market, and Ruprecht’s part-time job in marketing for Stone Ridge’s Hasbrouck House, and the forthcoming baby. I ask her for her time management secret, hoping for an easy answer. “I’ve learned there are some things I have to let go,” Ruprecht says, “to find a balance between everything.” She’s cut back on the millinery for now — custom orders only. In part, she says a focus on the syrup business “helps our family” more than the cumulative effect of all the other output. It’s strange to imagine something as easy to look past as what type of trees grow on your property could change one’s family, one’s work, one’s whole life. But when Ruprecht and her husband came to Laurel & Ash, they had their eyes open. And three years later, she sees lots of room to grow.